The Ōnin War: A Crisis for Gagaku Amidst the Turbulence of War

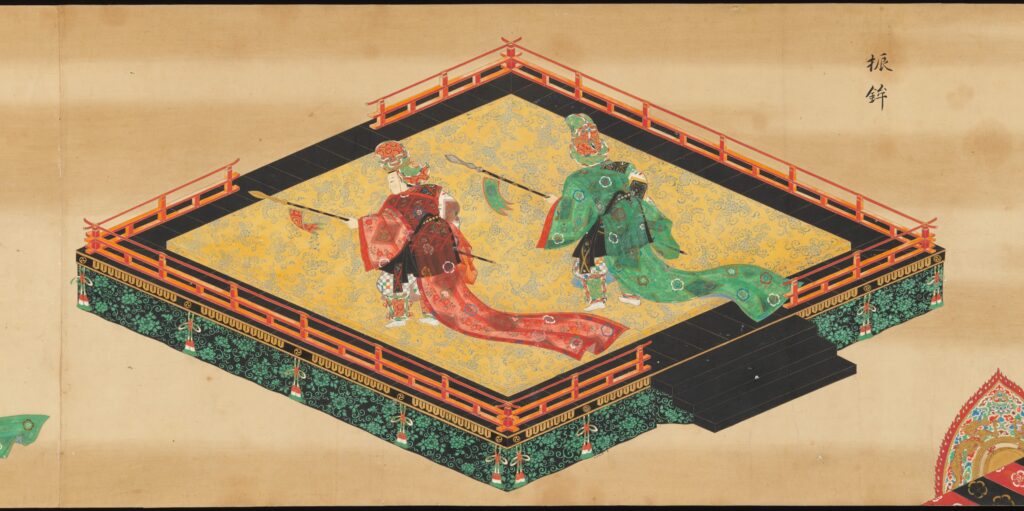

In the Heian period, gagaku (ancient court music) flourished within the aristocratic culture of the imperial court, shaping its form as we know it today. Even as the aristocratic influence waned and samurai rule emerged, passing through the Kamakura and Muromachi shogunates, gagaku survived under the patronage of the warrior class. However, as conflicts between samurai clans intensified, the country descended into chaos.

The Ōnin War (1467–1477) was one of Japan's largest internal conflicts, triggered by a succession dispute for the position of shogun. It pitted the Eastern Army, led by Hosokawa Katsumoto, against the Western Army, headed by Yamana Sōzen. Centered in Kyoto, the conflict resulted in widespread devastation.

A startling aspect of the warfare was the prevalence of arson as a primary tactic. Kyoto, once a thriving city, was reduced to ashes, with iconic landmarks such as the Golden Pavilion (Kinkaku-ji) and Kiyomizu-dera destroyed.

As Kyoto became a battlefield, the Muromachi shogunate’s authority diminished significantly, paving the way for the Sengoku period, where local warlords vied for power across the country.

Gagaku’s Endangered Legacy During Turbulent Times

The decline of the imperial court and the decline of traditional social structures during this period led to the loss of gagaku's oral traditions, ceremonial costumes, musical instruments, etc. The practice of gagaku, deeply tied to imperial ceremonies, was on the verge of extinction.

Amidst this crisis, in 1512, Toyohara No Muneaki (1450–1524), a gagaku musician in Kyoto, compiled Taigenshō (體源鈔), one of the three major treatises on gagaku, alongside Kyokunshō (1233) and Gakkaroku (1690). Written in the wake of the Ōnin War, Taigenshō was a lamentation for the state of gagaku and a determined effort to preserve its traditions.

Remarkably, it was the samurai, including prominent warlords, who played a pivotal role in reviving gagaku. Figures such as Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi actively promoted and safeguarded gagaku, ensuring its survival.

Oda Nobunaga and the Revival of Gagaku

In a society ravaged by warfare, where musicians had dispersed to rural regions and most manuscripts, costumes, and instruments were lost to fire, Nobunaga extended his support to gagaku. Hideyoshi continued this legacy, providing substantial protection and fostering its preservation.

Nobunaga’s patronage is reflected in gagaku artifacts. The kagura-byo (ornamental curtain) and costumes used in performances often feature Nobunaga’s family crest, the “Oda Mokko,” as a tribute to his contributions. The ceremonial attire for gagaku performers, such as hitatare (formal samurai clothing) and, also reflects respect for Nobunaga’s role in supporting gagaku.

The Tokugawa Shogunate and Institutionalization of Gagaku

Following the chaos of the Warring States period, the Tokugawa shogunate established order, and the imperial court regained some of its ceremonial functions. Emperor Ōgimachi engaged musicians from Osaka’s Shitennō-ji to restore gagaku performances for imperial rituals. In the Edo period, Emperor Go-Mizunoo summoned musicians from Nara’s Kōfuku-ji to supplement the court’s gagaku performers, establishing a system where musicians from Kyoto, Osaka, and Nara collaborated in ceremonial performances.

The Tokugawa shogunate institutionalized and financially supported this system, leading to the establishment of the Sanpō Gakusho (Three Regional Music Offices), ensuring gagaku’s continued practice.

Reflections on Gagaku’s Survival

The Tokugawa shogunate’s protection of gagaku raises intriguing questions. Why did warlords and shoguns devote themselves to the preservation of gagaku? Was it for political reasons? Was it a reflection of their spiritual beliefs? Or perhaps, a personal appreciation for gagaku as an art form, cultural legacy, and historical treasure?

It is likely that all these motivations intertwined. Gagaku may have held a profound ability to touch the hearts of people weary of turmoil, offering solace and a connection to a bygone era of peace and refinement.

Gagaku's enduring resonance suggests that it served more than just music; it may have been a symbol of hope and continuity amidst the chaos of war.

Written by Atsuko Aoyagi / ao.Inc.

#dailythoughts #japanesetraditionalmusic #composition

#gagaku #composinggagaku #nonmusic #gagakuperformance

#filmmusic #cinematicmusic #spatialmusic #gagakustories #sidenotes

#layer #mysterious #shogun #taroishida #shogun